A Less-Random Generator

In game development, it’s very common to want a random number. Maybe you want to determine damage done, if there was a critical, or what slot on the board to insert your piece at. And surprisingly (or perhaps, not), programmers are often looking to make this random number a little less… random.

Less Random, you say?

Yea, seriously. We really don’t want a real random number, because random is too random. Backgammon players rage on about how un-random virtual dice rolls are, and programmers can go to extreme circumstances to provide the right kind of random.

Role playing games have to overcome this too-random problem as well. In an RPG, you might be getting a random number to determine if the player character hit the monster. And considering the situations you find yourself in when playing an RPG, this dramatic but randomly generated experience can really suck:

A blade spider is at your throat. It hits and you miss. It hits again and you miss again. And again and again, until there’s nothing left of you to hit. You’re dead and there’s a two-ton arachnid gloating over your corpse. Impossible? No. Improbable? Yes. But given enough players and given enough time, the improbable becomes almost certain. It wasn’t that the blade spider was hard, it was just bad luck. How frustrating. It’s enough to make a player want to quit.

It’s really quite interesting how much we really don’t want real randomness. Because real randomness is not biased. Pure randomness doesn’t care if that’s your 20th “1” in a row. It can lead to frustration, and cause people to blame the game for sucking, when really it was just a bad sequence of random numbers.

How We Perceive Random

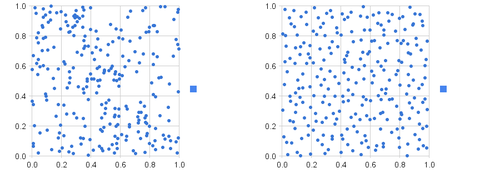

It turns out, when we say random, as a player, we actually mean controlled random. Compare these images of dots plotted on a grid:

Which picture looks like the random we want? Apparently, the first is too random for humans. What I mean is, it doesn’t look random. We quickly identify patterns in the truly random picture. We see groupings and think there must have been numbers that were favored to get that result. We want to believe that randomness will evenly distribute it’s results across the spectrum. No patterns, no missed numbers, no repeats. Even.

The truth behind these 2 images is that the left image is a true random plot. The image on the right was controlled.

The plot on the right is […] composed of 64 smaller squares, each of which has 4 points placed at random. People don’t like the leftmost plot because it has several clumps of points that seem non-random. In fact, true randomness consists of a mixture of clumps and non-clumps. Randomness is different from homogeneity.

A programmers solution

The way to handle controlled randomness is actually pretty simple. It’s commonly called a shuffle bag. The principle is that you take a bunch of tokens and put them in a bag. Then when you need another value, you pull a token out of the bag, and use that. Once the bag is empty, you fill it back up again.

You can control the percentage of a positive or negative result by setting the ratio of tokens you insert into the bag. You can also control what sort of “sprees” you can get from you bag by inserting duplicate values.

For example, with 1 hit value and 1 miss value, you have a 50% (½) chance of hitting. You also have the possibility of getting 2 misses or hits in a row. If you changed that to contain 5 hits and 5 misses in the bag, you could possibly end up with 10 in a row.

import random

class ShuffleBag(object):

def __init__ (self, values):

self.values = values

self.list = None

def next(self):

if (self.list is None) or (len(self.list) == 0):

self.shuffle()

return self.list.pop()

def shuffle(self):

self.list = self.values[:]

random.shuffle(self.list)

The usage would be pretty simple. If I want a 20% chance of getting a critical hit on a damage roll, I would implement that like so:

bag = ShuffleBag([1, 0, 0, 0, 0])

while attacking:

is_critical = bag.next()

if is_critical:

dmg = MAX_DMG

doDmg(dmg)

Who’d have thought that you needed to do something special just to get “fun” random numbers? I think the root of it has to do with how statistics are all just a lie.